7/23

Sub/Counterculture

Attempts at a unified totalizing formula of subculture will inevitably fall short in that they fail to adequately account for the specific intersecting historical and material phenomena which create the subculture. However it appears that no matter what form the subculture takes, no matter what specific elements feed into its development, and no matter its actual liberatory effect, some sort of dialectical process between the subculture and the containing culture does unfold, and it produces a form of the subculture that is somehow different. At the risk of encouraging notions of aforementioned formulae, I would point out for example that counterculture today means something different than it did in the 60s, punk culture means something different than in the 70s, house music (and post-punk music) means something different than in the 80s, techno/rave means something different than in the 90s, and so on. In this essay I would like to examine parallels between the way that highly visible subcultures enter into collective mythology, while foregrounding the distinctive elements of each. I would then like to touch on some of the radical, alternative ways that subculture could be approached in order to break out of cycles of its commodification.

Insofar as they are a product of the intersection of a variety of historical forces, each subculture manifests differently, leading to distinct functionality and signification. I would argue that at least some subcultures, namely, those that are most visible and accessible, relate to the culture that they are contained within similarly, though their principle function varies accordingly based on the context. Proceeding from this theory, this essay analyzes the major elements of a selection of prominent subcultures to develop a rough outline for how subcultures get produced and function.

To start, one fundamental similarity across subcultures is the intention of the cultivation of an alternative space, whether literally or figuratively. This appears to have been a primary outcome of the Chicago house scene: Salkind describes the clubs and venues where house music developed as "spaces for cultural maintenance" (Salkind, 51). For Hispanic and especially Black young people who had been alienated from religious institutions, mainstream gay clubs, and other spaces of cultural practice, these venues provided a safe space that did more than simply accommodate their complex identities. Through the careful deployment of ritual aesthetics and sounds that represented black queer identities, DJs cultivated a "dance floor spirituality" (61) that offered club goers a way out of the oppressive structures that dominated their daily lives. The hippies who flocked to Haight-Ashbury, Woodstock, and Drop City doubtless imagined a similar liberation, though whether they found it is a much more ambiguous question. And the infrastructure that developed around punk and post-punk music could also be conceptualized as a space that many young people, disillusioned with the prospect of a life of meaningless labor for a system they hated, could escape into. Of note is that subcultural spaces gain their significance through the intersection of certain historical forces, meaning this significance is somewhat ephemeral, and the spaces only existed as such for a limited time.

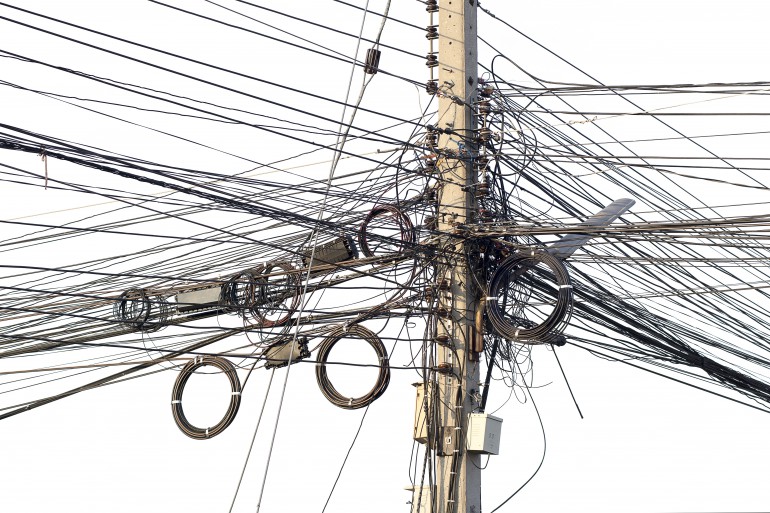

Along with attempts at carving out alternative spaces, another commonality among subcultures is a preoccupation with objects. Hebdige describes the process whereby mundane objects are imbued with a unique symbolic meaning as a "dialectic between action and reaction" (Hebdige, 2). The action is the appropriation by the subcultural group of certain objects and their integration of them into an abnormal context. For an example, in the punk subculture, which appears oriented towards objects to a greater degree than many other subcultures, we see objects like safety pins, fascist/communist symbols (made material in the form of clothing and pins), and BDSM wear pulled from the contexts to which the broader culture regarded them as fixed. The effect is a severe disruption of the "orderly sequence which leads from phenomena to their representation in the media" (90). To understand this process it is sufficient to attempt to empathize with the average member of the 1960s British bourgeoisie in their observation of punk style. Perhaps they would have seen the same pin they use to hold together their infant's diaper jabbed through a young persons septum, who also happens to be sporting a shirt depicting the symbol of an enemy ideology which had, for this upstanding citizen, up to that point been consigned to the newsreel and war film. In this moment there is an extreme shock to the symbolic order, along the lines of what the situationists were attempting.

The question then becomes what did these objects mean for the punks themselves? If these objects became imbued with symbolic meaning, what was it that they were symbolizing? The radicality of the punk's appropriation of these objects lies in the fact that they did not appropriate them for the express purpose of integrating them into a linear system of signified -> signifier -> sign, though this may have been a consequence at one point in the development of the subculture. To understand what the punks were doing we must examine their preceding subculture, namely, the preeminent sub-cultural movement of the 20th century: counterculture/hippie culture.

Adam Curtis rather dismally presents the neutering of this culture as the successful application by advertisers of research into psychoanalysis and crowd psychology. This research produced the advertising logic that many consumers sought to differentiate themselves through objects, and thus that the correct marketing response to the emerging demographic of people less interested in consumption than their parents was to develop a mode of advertising that made these people believe that they could express their individual qualities through the consumption of certain objects (Curtis, 27:00-29:00). It was in this way that the network of available commodities moved towards becoming GARAP-like, pure signifiers. That is not to say that such a process hadn't already began before this advertising revolution, nor is it to say that it did not continue after it, but it is certainly true that this was a point in which a much more expansive selection of objects truly began to express "form, color, shape, the accessories, and the 'social standing'" and to "speak their own idiom", rather than expressing their concrete structure, than had previously (Baudrillard, 15). To return to punks, who were experiencing this process: their subculture was an attempt to expose the logic underlying this process, whereby objects become pure signifiers, by appropriating seemingly mundane objects that were still attached to certain concrete contexts, and in doing so, severing this attachment completely, rendering the objects part of the empty language of GARAP (or quilt of floating signifiers, as Zizek as conceptualized it) for those outside of the subculture. For those inside the subculture, this became a style which "cohered elliptically through chain of conspicuous absences" (Hebdige, 120) . Cognizance of these absences, these disjunctions in the framework of signs that they were actively creating, is what enabled the punks to perceive a coherent style out of a paradoxically incoherent system of objects.

The foregone conclusion of such a process is the reintegration of these forms into "the dominant framework of meanings"(94). The shock that the punks deliver to the system unfolds on a very brief temporal scale, as this process of semiotic disruption, while providing the possibility of a radical break with this dominant framework of meaning (empty signifiers which relate only to other empty signifiers) through the creation of a style, inevitably primes the subcultural objects themselves for commodification. As Hebdige writes: "The creation and diffusion of new styles is inextricably bound up with the process of production, publicity and packaging, which must inevitably lead to the defusion of the subculture's subversive power" (Hebdige, 95). This material process ("the conversion of subcultural signs [...] into mass produced objects"(94)) runs parallel with the semiotic process where these objects, shorn from their original signified, can now be related to the existing networks of signifiers and turned into commodities like anything else. Punk objects and signs, then, come to represent the ethos of the style, but only insofar as it relates to other empty reference points (e.g. the abstract idea of authority, which has its own system of objects). They cannot recreate the semiotic disruption that gave the original movement its fangs.

The final major dimension of subculture that I would like to touch on here is the promise of some sort of radically divergent future. For the 60s counterculture, this took at times an eschatological form. The "hyperconscious historicity" of Manson's prophetic vision could be seen as this sense of impending change taken to an extreme conclusion (Verhoven, 270). For the hippies, as for most groups experiencing a subcultural movement, the intersection of a variety of historical forces really did provide a clear possibility for a different future. The merging of racism and Marxist teleology that Manson preached was insane, but it reflected the realities of his time. The activism undertaken by the Black American population at that time really did represent something fundamentally outside the dominant cultural milieu. The social tension there, and that which was generated by a population of young people who believed they could not live the lives they wanted to under the current system, represented potential for real change. However the time frame in which these forces had power is, once again, hopelessly brief. The civil rights movement did have its tangible, if small, victories that somewhat improved the lives of many Black Americans, however Black activism in its most radical form was violently suppressed. Much of the racism that these movements sought to combat remains entrenched in the institutions that shape our society. Giving the hippies a better system of objects seems to have been enough to direct their energies elsewhere, on top of the movement somewhat losing its way to drugs. Nevertheless, these "lost futures" (qua Mark Fischer) retain a certain mythic allure today. This allure is predicated on a nonrecognition of the specificity of the circumstances that allowed for the possibility of such a future in the first place: the "lost future" of a given subculture instead appears frozen in time, accessible to us through the simple consumption of certain commodities. This lie is familiar, but in it there is a kind of truth, a kind of liberatory potential that I will return to momentarily.

These are the three major elements of subculture that constrain it to a specific time period: spaces, objects, and futures. Each of the three elements crucially only has its full power in its original context. Through the commodification and mythologization of the subculture, this fact becomes obscured, inducing a "breakdown of temporality" where the subculture is frozen as as an image that can be eternally returned to:

"for political groups which seek actively to intervene in history and to modify its otherwise passive momentum [...], there cannot but be much that is deplorable and reprehensible in a cultural form of image addiction which, by transforming the past visual mirages, stereotypes or texts, effectively abolishes any practical sense of the future and of the collective project, thereby abandoning the thinking of future change to fantasies of sheer catastrophe and inexplicable cataclysm" (Jameson, 85)

Jameson's indictment of current politics here for the most part encapsulates this process. But the reduction of lost futures to mere "fantasies of inexplicable cataclysm" is a bit hasty. It may be true that in the commodity form of the subculture, this lost future really is just a fantasy. But "slumbering within the objects" are the symbols of a future envisioned by the collective unconscious of the groups that, however briefly, at one point possessed the means for bringing it about (Buck-Morss, 274). Accessing this requires "the child’s fantasy [...] cathected onto the products of modern production" (274). Benjamin's strategy for bringing this about, his arcade wanderings, seems rather tenuous today. Now the internet is the place where the "discarded dream images of mass culture" reside (273). Problematically, it appears that our engagement with images on the internet only facilitates the development of algorithms which in turn facilitate more engagement, to no productive end. Thus the strategy for rediscovering the political knowledge of neutered subcultural movements must involve a radically different engagement with the internet, an engagement that comes from the mental space of childlike fantasy.

Claudia Verhoeven - Now is the Time for Helter-Skelter

Dick Hebdige - Subculture: The Meaning of Style

Fredric Jameson - Postmodernism or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Jean Baudrillard - The System of Objects

Micah E. Salkin - Do you Remember House

Susan Buck-Morss - The Dialectics of Seeing