7/23

Playtime

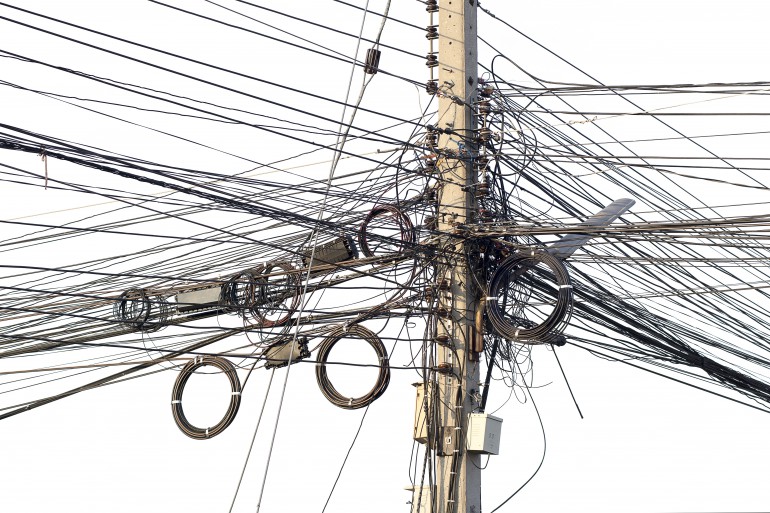

In Playtime, Tati presents the viewer with a carnivalesque vision of Paris as the archtypical capitalistic city. It is absurd in its homogeneity, its mechanistic functioning, and the behavior of its denizens, but it offers us pertinent insights into the nature of actually existing capitalist society. Although there are a number of incredibly rich scenes to analyze, the most critical point in the film is the nightclub sequence. What we are presented with throughout the film is a vision of a city, which, however surreal, empty, and chaotic it is, tends to cohere and work to produce a specific kind of controlled, efficient existence for the citizenry. Uniform lines of cars roll forwards as if in a military parade, workers attired in clothes of uniform similarity march through the streets, and various functionaries dutifully perform their little robotic tasks. When we arrive at the nightclub however, we for the first time observe a kind of breakdown of this system. This breakdown is not so absolute, however, as even through the chaos, the people continue to fulfill their social roles.

First there is the doorman's faithful charade with the handle from the shattered glass door (Tati, 1:27). Pieces of the door litter the empty frame, and yet the doorman insists on pretending, on continuing to keep up the appearance of a certain hierarchical social relation which is confirmed in the door ritual. Even though he is subordinate in this framework, and has the opportunity to literally break out of it presented to him by Hulot (whose status in this film as a wandering force of subversion is worth discussion), he goes to absurd lengths to maintain the illusion. And the bourgeosie guests are content to play along. Moving inside the venue, the general repugnance/lack of food provides another important insight. Part of the baseline justification for the entire spectacle of the nightclub is to feed its patrons. However, the food is unappetizing, unhygenically prodded by the waitstaff, and so limited as to force the kitchen to serve cold chicken even before all of the guests have arrived (1:24). This ends up mattering little to the diners, for whom what matters is the spectacle wherein the waiter seasons the fish in front of them. They have internalized that "all social life is mere appearance" (Debord, 14) to the point where a baseline human desire is negated. As the night progresses, the building continues to crumble(1:05, 1:35). Even as the ceiling falls and the floor breaks, the American shouts "the party goes on" (Tati, 1:41). Each of these details, and many more, serve to illustrate a dimension of a larger process: the continual engagement of a population of individuals with a system that is crumbling, nonfunctional, and harmful to everyone involved.

In this way, the scene serves as an allegory for Herbert Spencer's diagnosis of capitalist society ("There is no alternative"), an idea which has been rearticulated both zealously by politicians and pessimistically by many theorists. In this essay I will examine the contradictions within mass culture and modes of engagement with it that substantiate the notion of an unassailable system of mass culture/spectacle.

Since Descartes put traditional systems of truth on the chopping block with the radical doubt expressed in his philosophy, we have been hurtling towards an ever more refined positivism (qua Adorno & Horkheimer). The rationality of the enlightenment, along with its new modes of truth creation, demanded a revolution in the social order. It was necessarily a revolution that aimed to move from the spiritual to the rational, the essential to the particular, the fluid to the fixed, and so on, as this was what the philosophical revelations of the enlightenment commanded. It did this by radically reconceptualizing truth creation and thought, directing such processes towards the attainment of a "form of knowledge which most ably deals with the facts, most effectively assists the subject in mastering nature"(Adorno & Horkheimer, 65). The consequences of this kind of thinking were not constrained to intellectual disciplines, containing as they did implicitly such complete indictments of non-positivist thought. All social life was slowly taken over through the "incessant deployment of the very technical rationality to which [Western] philosophical tradition gave rise" (Debord, 17). Debord identifies this as a kind of philosophization of reality (17).

The broad contradiction lies in the fact that prima facie, this philosophy defends individuality, freedom, and humanity, but as its principles are fully realized, fascism in its antithesis emerges as a logical step. Adorno and Horkheimer describe this process: "once reason had been formalized, pity was left behind as a kind of sensuous awareness of the identity of general and particular, as naturalized mediation" (Adorno & Horkheimer, 79). Thus pity and other such impractical judgements became irrational because "{they are} the opposite of the manly competence which, from Roman virtus through the Medici to efficiency under the Fords, has always been the true bourgeois virtue" (79). This "competence" as an absolute ideal gives way to logics of fixation, hierarchization, and other general violence. Even the enlightenment's own ideals, namely, essential and universal rights protecting the freedom of the individual, are quickly usurped by this totalizing logic. Fascism only fails because it is suboptimal: social organization under postwar forms of capitalism turns out to more totally realize positivism. It does this through a highly complex, cybernetic control system that has been variously referred to as the spectacle or culture industry.

The culture industry is nebulous in its functioning, but it is sufficient for the scope of this essay to touch on a selection of Adorno & Horkheimer's points. The first is homogeneity. Central to their thesis is that "Each branch of culture is unanimous within itself and all are unanimous together" (Adorno & Horkheimer, 94). Seemingly one does not have to go very far into the media to refute this, after all, the form and content of culture is superficially variable: We have evolving mediums, variegated genres, artistic movements, and a discourse of assenting and dissenting philosophies expressed in the cultural arena. However what is really critical for understanding this contention is a formulation of the spectacle (I am defining the spectacle and the culture industry as synonymous) as a process. The spectacle is described by Debord as "the total practice of one particular economic and social formation" (15). It is not simply the output of the culture industry, rather it is the inputs, the process of culture/spectacle generation, and the real social activity that is catalyzed by its consumption that represent spectacle. It is this system that is unified and homogeneous. Everything goes into it, including dissent, because every single resource and social process is mobilized in the service of the culture industry. This is why Adorno & Horkheimer write that "Anyone who resists can survive only by being incorporated" (104). Real activity in the face of this is always the same: it is more consumption. Despite the various social movements, protests, legislation, and changing morality, the fundamental social organization among rich western nations (read: property relations) has not changed significantly since the mid 19th century. This attests to Adorno & Horkheimer’s axiom. All truly radical politics and praxes have been sublimated to a form that can be consumed without significantly disrupting property relations. They have been confined to the university and stuffy intellectualism that remains painfully out of touch with mass society, they have been metamorphosed into fake ideological issues that politicians and voters engage with, and they have been wielded by advertisement as consumer identities (think punk, hippie, alternative). Another broad contradiction: despite the free expression ostensibly afforded to individuals in this kind of society, the process of mass culture or the culture industry induces a sort of proscrutization wherein the idea is forced into a particular mode of expression that renders it inert.

How can such a system defend itself? It mobilizes nothing less than one of the most enduring forms of western art: tragedy. By essentializing tragedy, the particular effects of the system become universal truths about the functioning of the universe. First there is the suffering under capitalism:

"Far from merely concealing the suffering [...], the culture

industry stakes its company pride on looking it manfully in the eye and

acknowledging it with unflinching composure. This posture of steadfast

endurance justifies the world which that posture makes necessary. Such is

the world—-so hard, yet therefore so wonderful, so healthy." (122)

Property relations which induce this suffering are obscured completely, replaced with the malignant "that's life" platitude. To complete the arrangement the role of the tragic figure, who resists in vain, is assigned to "neighbors, social welfare officers, Dr Gillespies, and armchair philosophers with their hearts in the right place" (121). To not engage with such characters is to subject oneself to tragic punishment (thus the indignation towards the poor). To engage and even become like them, perhaps realizing bourgeoisie existence, is to subject oneself to a slightly different set of anxieties, which, however mitigated by the material comforts that society affords conformists, stem from the same control process. Both groups are subjected by "the spectacle of implacable life and the exemplary conduct of those it crushes"(123).

There is one further element of the control system worth noting here. It is the process through which we approach the consummation of the total dehumanization that sets up the final leg of the dialectic between humanity and positivism. Total dehumanization is approached through what Baudrillard describes as a "'philosophy' of self fulfillment" which replaces early capitalist competition (12). In a society which has been further integrated and thus lacks the scarcity of previous eras, everyone can consume, thus the purpose of life is not competition, but instead the actualization of oneself in consumption (12). More contradictions: ""Free to be oneself" in fact means: free to project one's desires onto produced goods" (13). What is critical about this process is that produced goods are basically all GARAP: they are empty signifiers. Sure some consumables may be in one way material goods, and thus also "objects of need and satisfaction" (21). But satisfying a need with a material good is only a part of the consumption process. What completes it is the projection of a drive onto the object as an image (empty signifier, GARAP). The effect is that

"drives that were previously blocked by mental determinants (instances) (taboo,superego, guilt) [are allowed to] to crystallize on objects, concrete determinants where the explosive force of desire is annulled and the ritual repressive function of social organization is materialized." (13)

The externalization of these drives has the effect of psychologically freezing people. Rather than going through or traversing these mental determinants/complexes to access the liberatory potential that these drives have for the individual, they are frozen in an empty state where their drives are tortuously all around them in their system of objects, but fundamentally inaccessible. This is the hollowing out of humanity which renders us as raw material for the further development of positivism.

It is a cruel irony that humanity plots a downward spiral along some of the things which make us most human. Philosophy, which represents the ever distinctive curiosity of humanity, and can be seen as a high level thought form that math, science, and art are subordinate to (they become philosophy at high levels), flips over into the ultimate banality of optimization. Tragedy, which, at least in western cultures, has been an expression of the human condition across time and (some) context(s), becomes perversely real as an impenetrable ideology. And the drives that provide the closest criterion for defining humanity are dissected out in a process that renders us inert consumers. History since the enlightenment has been a dialectic between humanity and positivism that unfolds along these lines. Chillingly, it appears as if it will resolve not through a synthesis, but through the elimination or at least obsolescence of humanity.

Debord, Guy. “Seperation of the Spectacle.” Society of the Spectacle, Black & Red, 1977,

pp. 12–24.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by Edmund

Jephcott, Stanford University Press, 2002

Poster, Mark, and Jean Baudrillard. “The System of Objects.” Jean Baudrillard: Selected

Writings, Polity Press, 1988, pp. 10–56.

Tati, Jacques, director. Playtime. Specta Films, 1967.